How an old smartwatch found new life when the hackers that loved it, decided not to let it die

Two weeks ago I spent $40 on a 5-year-old smartwatch from a now-defunct company with dead servers, no app, & zero support. All that aside, it's actually one of my best eBay finds this year. I’ve been collecting watches for over a decade, but when a timepiece enters my rotation it isn’t to stunt on strangers. I prefer to collect watches that have a story. Most often it’s due to the role they played in history, but on occasion, it's because of the story of the company that made them. That is what drew me to Pebble; a watch that for many is another footnote in the long history of tech’s blitzkrieg march toward obsolescence. But to me, this footnote is also a manifesto.

Most smartwatches are desperate cash grabs from big companies like Apple and Samsung to capitalize on the emerging market of wearable tech. They are capable — sure — but they all feel uninspired. What hooked me about Pebble wasn’t just the vision, but its aftermath. The way its corpse was resurrected by hackers, coders, and FOSS fanatics when the suits walked away. Pebble’s second act isn’t just a comeback. It’s a parable. To understand why this dead gadget matters — why I’d buy a eulogy in plastic and silicon — we need to go back to where it all began.

The Watch That We Deserve

Today, the tech market is flooded with a spectrum of smartwatches offering all the features (and gimmicks) you could desire, but this wasn't the case back in 2012. For decades prior, there were grandiose visions for what a smartwatch could be; from the 2-way radio communicator of Dick Tracy to the do-anything spy watches of James Bond. In ‘85 Sinclair released an FM radio wristwatch, and in ‘98 IBM released their “Linux wristwatch”. The one thing all these early experiments have in common is that they were rarely ever more than concept devices. On the rare occasion that they were actually sold to the public, they moved in extremely low numbers. Then comes 2012 which marks a long-awaited milestone needed for this tech to become reality. Silicon processing chips needed to make digital electronics had finally hit the sweet spot of being small enough to conceal in something wrist-sized, efficient enough to achieve reasonable power consumption, lightweight enough to be forgotten about, and most importantly cheap enough to finally bring the dream of a general use smartwatch to life for real consumers. Faced with the ability to make some of the world's first true smartwatches, the tech industry had to find good ways of building a watch that was both cool and functional. The first implementations of this wearable tech were embodied in fitness trackers like the Nike+ Fuelband.

These units made sense because pedometer sensors (step-counters) are extremely low-power and could be used to roughly approximate calorie usage and other relevant health info that gave an obvious use-case to the athletic and sporty types. Later, Sony would introduce their first wearable known only as the “Sony Smartwatch” (model MN2SW). This unit included the first true color display in a wearable and drummed up some good press at launch, but ultimately it wasn’t very well-received by consumers because it tried to do too much with too little. The result was a watch that could do a bunch of things, but it didn’t do any of them particularly well, which meant in practice, using it was frequently more trouble than it was worth.

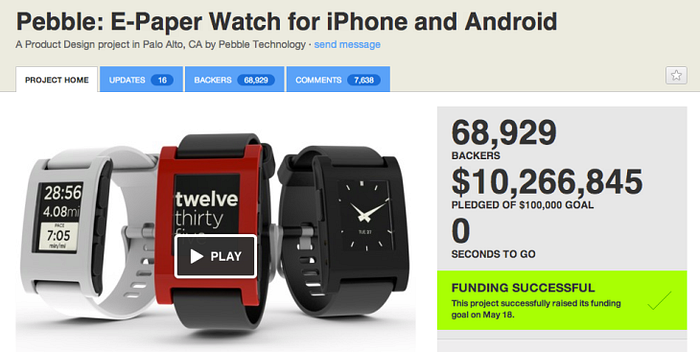

Finally came Pebble. In April of 2012, a Kickstarter campaign was launched by the very new Pebble Technology Corporation for an affordable and versatile smartwatch that planned to act as an extension of your phone rather than a replacement for it. This smartwatch, called only “The Pebble”, seemed like it might be the first wearable to actually deliver on the hype, and people were excited. So excited in fact, that the original Kickstarter funding goal of just $100,000 was obliterated as the campaign raised more than $10.3 million in a single month, instantly becoming (at the time) the most successful funding of a project in Kickstarter history. The people had decided that Pebble wasn’t just the watch that we wanted, it was the watch that we deserved.

First Impressions Are Important

Pebble began shipping the first units to Kickstarter backers in January of 2013. It was time to see if Pebble could live up to what they had promised. The original Pebble watch wasn’t winning any awards from fashion magazines, with a blocky plastic exterior that was more reminiscent of a child's toy than a high-end wristwatch but what it lacked in sex appeal it more than made up for on the inside.

The first strong point for Pebble was their decision to use a pixel Sharp Memory transflective LCD display instead of a full-color display like Sony. This display technology is more commonly referred to as “e-paper”, not to be confused with the e-ink displays that can be found inside e-readers like the original Amazon Kindle. Pebble’s e-paper display functions much like a normal LCD screen, but with two major improvements that make it perfectly suited for a smartwatch. Firstly, it's transflective, which means the display can either emit light internally using a backlight like a more traditional LCD or reflect external light through the pixel array for display purposes in brighter conditions. This allows the screen to remain easily readable outside, including in harsh direct sunlight where other watches struggle. When inside or in darker environments the backlight kicks on and the display continues to be easy to see. Secondly, when normal LCD displays update they have to redraw all the pixels for every frame. Pebble’s e-paper display had a memory function which meant they only needed to re-draw the pixels that actually changed from one frame to the next. By using this technology as opposed to AMOLED or traditional LCD’s the Pebble didn't waste energy powering a backlight constantly or updating pixels that didn’t change. The end result was that Pebble’s battery life demolished the competition, needing on average only one charge every 5–7 days as compared to even modern smartwatches which struggle to achieve 36 hours. In addition to this, it was entirely compatible with both iOS and Android. It performed fitness tracking through its 3-axis accelerometer with some help from your phone's GPS and It also did all the typical smartwatch things you‘d expect like showing your notifications, letting you see/answer calls, and controlling your music from any app via Bluetooth. Pebble also released a completely open SDK (Software Development Kit) that allowed any third-party developer to easily build and deploy apps to extend the watch’s functionality. Because of the ease of development and Pebble’s quick mass adoption, big companies like Uber, TripAdvisor, and Runfit quickly developed apps for Pebble, which lent a lot of legitimacy to the watch and its software platform. The main thing Pebble got right was striking the proper balance of utility and fun. It didn't try to replace your phone, it just gave you a lot fewer reasons to reach for it throughout the day.

Up, Up, and Away!

The Verdict was in, people loved Pebble. After the wave of support they received by releasing the original Pebble watch, the company grew and continued to innovate. Over the next 4 years, they began releasing new and improved models. The main complaint about the first-gen Pebble was the homely plastic exterior. Because of this, the next model they released was the Pebble Steel. The same watch you know and love, but dressed up in a sleek new stainless steel chassis and metal clasp band. The Steel was the first version of the pebble I owned, and it was the only tech in my life that I was excited enough about to brave a black Friday line for.

Okay, that's all well and good, but what about color and smoother animations? No problem, Pebble responded, while announcing the Pebble Time on Kickstarter. This Model had the massive improvement of an e-paper display with 64 colors as well as a re-designed OS with smoothed animations and a new timeline feature. The timeline provided an easy way for you to keep track of your notifications and upcoming events. They also added some minor features like a microphone for text-dictation. Through all these updates Pebble made sure to stay true to its roots as a battery beast, meaning the Pebble Time, even with its many upgrades, could still go 5-7 days between charges. When the Kickstarter for the Pebble Time went live, they hit their funding goal of $500,000 in just 17 minutes, finished the first hour with over $1,000,000, and closed out March with $20,300,000. The unimaginable success of their crowdfunding meant they had shattered their own Kickstarter record and to date, the pebble time is still the most successful funding of a project to ever take place on the platform.

In the years that followed, Pebble continued to announce and release several more models but eventually ran into some trouble.

Icarus

The year is now 2016, and the landscape of wearable tech is lush and vibrant. Thanks in large part to Pebble’s early success paving the way for bigger companies by proving the smartwatch market was more than mere bluster. In a product space now filled with offerings from goliaths like Samsung, Motorola, and Apple, Pebble’s market share began to fall. After the victory of the Pebble Time, subsequent models failed to achieve the same level of critical success and over time users began turning to other players in the smartwatch field. This created money problems for Pebble and unfortunately marked the beginning of the end for the Wunderkind brand. On December 7th, 2016 FitBit, a company that makes a series of very popular wrist-mounted fitness trackers, completed their purchase of Pebble for a mere 23 million dollars. Fitbit absorbed some of Pebble’s valuable intellectual property as well as some key staff before eventually shutting the company down. When this acquisition was announced, they claimed that Pebble watches wouldn’t experience any immediate changes but ominously mentioned that “Pebble functionality or service quality may be reduced in the future”. When Fitbit completed their vampiric exfiltration of anything valuable from Pebble, they powered down the servers that run the Pebble app and watch face marketplace as well as the servers that provided the watches with the weather and other useful API data. This meant that anyone who had a Pebble lost significant functionality overnight and many took their watches off for the last time.

Rebble With A Cause

When Pebble shut down there was still a large and passionate group of hackers, tinkerers, developers, and general tech enthusiasts that loved their quirky little smartwatches. Pebble always had a core base of power users who liked the watch for its geek aesthetic and “hackability”. Unwilling to let their favorite watch dissolve into the void of the forgotten tech from yesteryear they banded together into a ragtag coalition united under the singular mission of saving pebble smartwatches. This new alliance called themselves Rebble, a play on words rhyming with the watch's original. Chief among the original developers of Rebble was Katharine Berry, a former employee of Pebble and a true believer in the technology they had developed. Fearing the day Fitbit would flip the kill switch, Kathrine worked tirelessly to archive and document whatever she could of the Pebble watch’s firmware and the company’s original development assets. By collaborating with a community eager to help as well as several current and former employees of Pebble and Fitbit, the race was on to build a set of web services that would allow Pebble users to continue full use of their watches after the original server got switched off. For two straight weeks, they tinkered away in a hackathon that ultimately ended in having successfully built a completely free alternative to Pebble’s original web services. This meant that with minimal effort a user could switch their Pebble watch to Rebble services and continue to use it for as long as they like. Rebble even offers additional Weather and Dictation services for a small fee (as running these services costs them a lot of money) so the power users can get extra features while supporting the alliance.

Conclusion

There was a time in years now gone when the prevailing economic theories told us that markets were driven by the consumer. It was we who decided what was worth buying, and when it stopped being made. We would “vote with our wallets” as they say. It is debatable if this was ever actually the case, but regardless of what once may have been, we can be certain that is not the case now.

Consumers in the modern market are so rarely the subject that acts, rather than the object that is acted upon. The story of Pebble and its rebirth as The Rebble group is a case study in consumer agency. Crowd-funded from day one and saved from the dead, it serves as a reminder that we still have the capacity, the right, and — I would argue — the obligation to be the ones who shape our own technological destinies. The way we interact with the world is mediated by the tools we use to operate within it. You may think “It’s not that deep”, but I have seen time and time again how much changing the tech I use changes the way I act when I use it.

There is real power in our collective willingness to refuse obsolescence, to stand up for our right to stop perfectly good gear from rotting in a landfill. This isn’t just a matter of preserving nostalgia for a fun little gadget; it’s about preserving our right to dissent, to create, and to reclaim space in an industry that seems to have forgotten that we are more than just consumers. That may seem like a lot of pressure to put on a quirky smartwatch from a dead company, but when I roll out of bed each morning and slip it on my wrist, I am reminded of the power of a Rebble, and I think that is a good thing.